On 27th January, Prime Minister Herbert Asquith’s government passed the 1916 Military Service Act and introduced conscription to the British Isles. It came into force on 2nd March, 1916. Previously the British Government had relied on voluntary enlistment, and latterly a kind of moral conscription called the Derby Scheme.

Lord Horatio Herbert Kitchener, Britain’s secretary of state for war, had warned from the beginning that the war would be decided by Britain’s last 1 million men. All the regular divisions of the British army went into action in the summer of 1914 and the campaign for volunteers based around the slogan “Your King and Country Need You!” began in earnest in August of that year. New volunteers were rapidly enlisted and trained, many of them joining what were known as Pals battalions, or regiments of men from the same town or from similar professional backgrounds. Though the volunteer response was undoubtedly impressive—almost 500,000 men enlisted in the first six weeks of the war alone—some doubted the quality of these so-called Kitchener armies. British General Henry Wilson, a career military man, wrote in his diary of his country’s “ridiculous and preposterous army” and compared it unfavourably to that of Germany, which, with the help of conscription, had been steadily building and improving its armed forces for the past 40 years. By the end of 1915, as the war proved to be far longer and bloodier than expected and the army shrank—Britain had lost 60,000 officers by late summer—it had become clear to Kitchener that military conscription would be necessary to win the war. Asquith, though he feared conscription would be a politically unattractive proposition, finally submitted. On January 5, 1916, he introduced the first conscription bill to Parliament. It was passed into law as the Military Service Act on January 27th 1916 and went into effect on February 10th.

The Labour Party held a conference in Bristol on the 27th Jan 1916 and at the conference a card-vote division on conscription resulted in 219,000 votes in favour of universal military service, and 1,796,000 against it. The bill enforcing compulsory service in only single men was favoured by 360,000 votes and opposed by 1,716,000. But a proposal to agitate for repeal of the Bill was opposed by 649,000 votes and favoured by 614,000 votes. There was thus a majority of 35,000 votes tacitly consenting to the compulsion Act for single men being put in force. As one representative put it: “These divisions mean we Labour men are very angry, but we don’t intend to do anything”

The Act specified that men from 18 to 41 years old were liable to be called up for service in the army unless they were married, widowed with children, serving in the Royal Navy, a minister of religion, or working in one of a number of reserved occupations. The second Act on 25th May 1916 extended liability for military service to married men, and the third Act in 1918 extended the upper age limit to 51. The Act was modified by subsequent legislation throughout the First World War, and conscription continued until 1920

The following categories were established:

A: General Service.

B1: Garrison Service Abroad.

B2: Labour Service Abroad.

B3: Sedentary Work Abroad.

C1: Garrison Service at Home Camps.

C2: Labour Service at Home Camps.

C3: Sedentary Service at Home Camps.

The Official History records the physical standards defining each category:

A: Able to march, see to shoot, hear well and stand active service conditions.

B: Free from serious organic diseases, able to stand service on the lines of communication in France, or in garrisons in the tropics.

B1: Able to march five miles, and see to shoot with glasses and hear well.

B2: Able to walk five miles to and from work, see and hear sufficiently for ordinary purposes.

B3: Only suitable for sedentary work.

C: Free from serious organic disease, able to stand service conditions in garrison at home.

Men or employers who objected to an individual’s call-up could apply to a local Military Service Tribunal. These bodies could grant exemption from service, usually conditional or temporary. There was right of appeal to a County Appeal Tribunal.

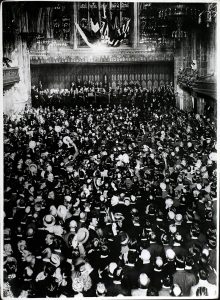

Conscription was not popular and in April 1916 over 200,000 people went to Trafalgar Square to demonstrate against it in. Although many men failed to respond to the call-up, in the first year 1.1 million enlisted.

Britain had entered the war believing that its primary role would be to provide industrial and economic support to its allies, but by war’s end the country had enlisted 49 percent of its men between the ages of 15 and 49 for military service, a clear testament to the immense human sacrifice the conflict demanded.