Founded on April 1st, 1918 during the First World War, the RAF is the oldest independent air force in the world. On April, 2018 our nation came together to recognise 100 years’ worth of innovation, comradeship, dedication, sacrifice and achievements.

The centenary itself was marked by special events, activities and other initiatives at local, regional and national level running from April to the end of September 2018.

History of the RAF

On April 1, 1918, the British Royal Air Force (RAF) is formed as an amalgamation of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS). The RAF took its place beside the British navy and army as a separate military service with its own ministry.

In April 1911, eight years after the American brothers Wilbur and Orville Wright made the first-ever flight of a self-propelled, heavier-than-air aircraft, an air battalion of the British army’s Royal Engineers was formed at Larkhill in Wiltshire. The battalion consisted of aircraft, airship, balloon and man-carrying kite companies. In December 1911, the British navy formed the Royal Naval Flying School at Eastchurch, Kent. The following May, both were absorbed into the newly created Royal Flying Corps, which established a new flying school at Upavon, Wiltshire, and formed new aeroplane squadrons. In July 1914 the specialized requirements of the navy led to the creation of RNAS. Barely more than a month later, on August 4, Britain declared war on Germany and entered World War I. At the time, the RFC had 84 aircraft, while the RNAS had 71 aircraft and seven airships. Later that month, four RFC squadrons were deployed to France to support the British Expeditionary Force. During the next two years, Germany took the lead in air strategy with technologies like the Zeppelin airship and the manual machine gun. England’s towns and cities subsequently underwent damaging bombing raids and its pilots were defeated in the skies by German flying aces such as Manfred von Richthofen, dubbed The Red Baron. Repeated German air raids led British military planners to push for the creation of a separate air ministry, which would carry out strategic bombing against Germany. On April 1, 1918, as a result of these efforts, the RAF was formed, along with a female branch of the service, the Women’s Royal Air Force (WRAF). By the war’s end in November 1918, the RAF had dropped 5,500 tons of bombs and claimed 2,953 enemy aircraft destroyed, gaining clear air superiority along the Western Front and contributing to the Allied victory over Germany and the other Central Powers. It had also become the largest air force in the world at the time, with some 300,000 officers and airmen—plus 25,000 members of the WRAF—and more than 22,000 aircraft.

RAF WW2

Everyone knows about the Battle of Britain, and how ‘the Few’ saved the country from invasion. What they don’t necessarily remember is that every one of the fighter pilots mentioned in Churchill’s ‘the Few’ speech had a team of dedicated ground crew, RADAR operators, WAAFs and many more behind him, and that Fighter Command, however much they were feted after the war (entirely deservingly) were not the only ones mentioned in his speech on August 20th, 1940:

“The gratitude of every home in our Island, in our Empire, and indeed throughout the world, except in the abodes of the guilty, goes out to the British airmen who, undaunted by odds, unwearied in their constant challenge and mortal danger, are turning the tide of the World War by their prowess and by their devotion. Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.

“All hearts go out to the fighter pilots, whose brilliant actions we see with our own eyes day after day; but we must never forget that all the time, night after night, month after month, our bomber squadrons travel far into Germany, find their targets in the darkness by the highest navigational skill, aim their attacks, often under the heaviest fire, often with serious loss, with deliberate careful discrimination, and inflict shattering blows upon the whole of the technical and war-making structure of the Nazi power. On no part of the Royal Air Force does the weight of the war fall more heavily than on the daylight bombers, who will play an invaluable part in the case of invasion and whose unflinching zeal it has been necessary in the meanwhile on numerous occasions to restrain.”

There’s no doubt that the fighter pilots were a heroic bunch, and that the work of the ‘Aces’ did a lot to boost the morale of beleaguered Britain. Douglas Bader was, of course, particularly well-known for the fact that, despite having his legs cut off after a plane crash in 1931, he went on to gain the Distinguished Flying Cross with Bar, not to mention the Distinguished Service Order with Bar, and shoot down 23 enemy aircraft. Additionally, he was the co-creator of the ‘Big Wing’ tactics, which involved sending a strong force to intercept enemy pilots over the Channel, and once captured, escaped the clutches of the Germans so many times that they were forced to confiscate his prosthetic legs. However, as John Rawlings asserts in his ‘Fighter Squadrons of the RAF’, for every high-scoring Douglas Bader there was a much less celebrated ‘Number Two’ who shadowed and guarded the tails of the attacking planes, allowing the ‘Aces’ to do their job to the very best of their abilities.

Although Churchill mentioned the work of bombers in his speech, Bomber Command was far less lauded after the war, as the government was squeamish about praising those who had flattened the German capital and caused many civilian casualties. This was, of course, part of their allotted role in the war, but the pilots and crews did much more than bomb cities. They destroyed communications systems to hamper the efforts of German Command, as well as bombing the factories producing the very planes that would spar with the fighters over Britain and the bombs that would be dropped onto soldiers and civilians alike. Also, crucially, it was they who bombed Berlin, throwing Hitler into a rage that would cloud his judgement and lead him to direct the German bombers to stop tackling British airfields, RADAR stations and factories and instead begin bombing London. While this assault was terrible, it gave Fighter Command the chance to step off its back foot for a while, reinforce, retrain and assess their tactics, and come back stronger against the Luftwaffe; without this opportunity, Fighter Command would likely have been crushed entirely in the autumn of 1940, and Operation Sealion, the invasion of Britain, might have succeeded.

Both Fighter Command and Bomber Command would have been, literally and figuratively, completely lost without RADAR. The RAdio Detection And Ranging system acted as the eyes and ears of the aircrew, and without the help of the operators to help them locate attacking enemy aircraft in the (very large) skies, such a small number of planes as were available in the early summer of 1940, post-Dunkirk, would never have been able to tackle the numerically superior and highly experienced Luftwaffe fighters. Air Chief Marshall Dowding was able, with their help, to conserve his valuable planes and pilots, and so nurse the RAF through June and July until more planes could be produced. Nor were the workers on the ground necessarily safer than the men in the air, as RADAR stations were targets, and the brave operators often refused to abandon their posts, even in the midst of the very heaviest bombing. Later in the Battle of Britain, the role of RADAR became even more critical, as the Germans began night bombing. As the introduction of ‘The WAAF in Action’ explains, “The radiolocation system of warning is very desirable in aerial warfare by day, but for aerial warfare, at night it is absolutely essential.”

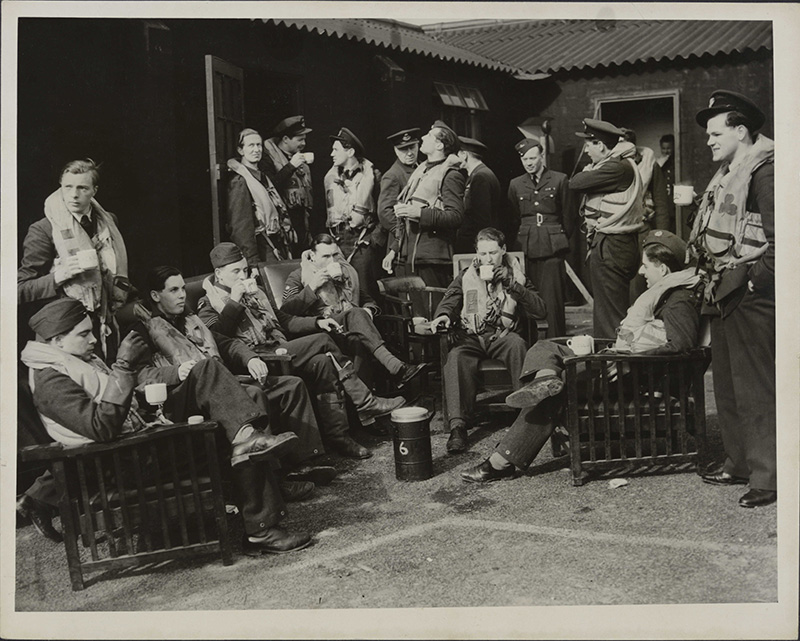

Another essential element of the RAF was the largely unsung ground crew. Whenever the pilots were in the air, the ground crew were also hard at work, directing battered aircraft into land and patching them up so that they were fit to fly, fuelling and servicing the planes, and ensuring that the guns were in tip-top working order. The Royal Air Force veteran Stan Harthill said, “The ground crew felt we had a very important part to play in the Battle of Britain because our job was to keep the Spits flying, and without the Spits, the pilots were of course useless.”

How true… a pilot is nothing without his plane, which leads us to one final lot of unsung heroes, the designers and factory workers who built the Spitfires and Hurricanes used to defend Britain (as well, of course, as the Lancaster’s). Thanks to the efforts of Lord Beaverbrook and these excellent workers, our output of planes far outstripped that of Germany, and as Norman Ferguson attests in his ‘The Second World War: a Miscellany’, in June 1940 we produced 446 new aircraft to Germany’s 220.

Bomber Command suffered a higher casualty rate than any other part of the British military during the Second World War and almost half of those serving with Bomber Command died, many killed by night fighters and anti-aircraft fire in raids over occupied Europe. 55,573 young men died flying with Bomber Command, that’s more than those who serve in the entire Royal Air Force today.

If the men of Bomber Command equalled those in RAF Fighter Command in usefulness, they officially overtook them when it came to bravery. Just one Fighter Command pilot was awarded a Victoria Cross in World War Two, compared with 23 Bomber Command airmen.

Fighter Command was established in July 1936 under the command of Sir Hugh Dowding. During World War Two, Fighter Command earned great fame during the Battle of Britain in 1940, when the Few held off the Luftwaffe attack on Britain.

It should never be forgotten that these young men carried the unceasing war to the enemy against fearful odds for over five years, and for much of that time alone while we lacked the means for any other attack.

The centenary itself will be marked by special events, activities and other initiatives at local, regional and national level running to the end of September 2018.

Did your ancestor fly above the trenches of the Western Front during the Great War, or chase the Luftwaffe attackers from the skies above Britain?

Forces War Records may hold the answer.

RAF100 Appeal.

The RAF100 Appeal is a joint venture between the Royal Air Force and four major RAF charities – the Royal Air Force Benevolent Fund, the Royal Air Forces Association, the Royal Air Force Charitable Trust and the Royal Air Force Museum. The aim of the Appeal is to raise money for the RAF Family and to create a lasting legacy as we celebrate 100 years of the Royal Air Force in 2018.

Find out more about the legacy of the RAF100 Appeal.

Numerous activities and events will be taking place across the UK until the end of September 2018. The Appeal forms part of the wider RAF100 initiative that seeks to commemorate the achievements of the RAF and all those who have served while at the same time celebrating the vital contribution that the RAF continues to make, and inspire both the public and the RAF Family as we look forward to the next 100 years.