Throughout history children have ended up on the battlefield, sometimes because they wanted to be there, and sometimes because they were coerced or forced to take part in the fighting. In Western society, at any rate, the position since the First World War has officially been that children should never, ever be seen participating in active service. However, at different periods the rules have been enforced with varying degrees of stringency, and the history books have shown that, invariably, when the chips are really down, the policy tends to revert to ‘anything goes’.

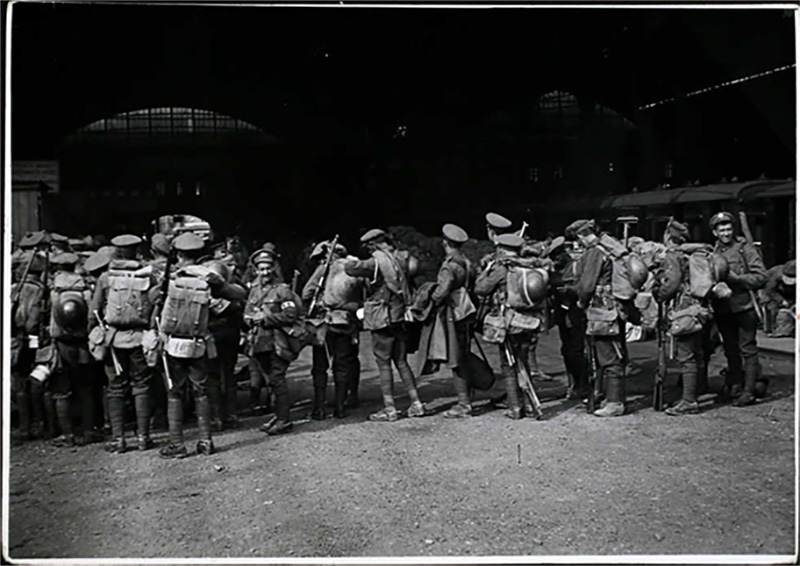

In the Great War, essentially every participating nation’s armed forces sported a healthy percentage of ‘keen as mustard’ youngsters. According to the WW1 Boy Soldiers site, when the war began in 1914 Great Britain had 700,000 men ready to fight, compared to Germany’s 3,700,000. Of course, the country was lucky enough to have an empire to call on for more men, but all the same, Field Marshall Lord Kitchener estimated that another 500,000 home troops must be raised at once to give Britain any chance of challenging the Axis forces. The need for able fighters was so desperate that many recruiters ignored the age limits, and instead went by the far more flexible height and chest regulations (over 5 foot 3 inches, and above 34 inches), or even occasionally tipped the wink to completely unsuitable candidates, if they seemed passionate about being given the chance to serve. Many people couldn’t afford birth certificates and didn’t have passports at the start of the 20th century, so it was not easy to prove someone’s identity, and boys were able to lie not just about their age, but sometimes even about their name (to avoid being traced and brought home by anxious parents). Between 1914 and 1916, it has been estimated that some 250,000 soldiers below the stipulated 19 years of age signed up to fight. From March 1916, the age limit dropped to 18 for the rest of the war, but never below.

Prior to 1916, young men rushed to join the Armed Forces for a variety of reasons. One was intense peer pressure, as James Leslie Lovegrove explains in a podcast held by the Imperial War Museum. Lovegrove first tried to enlist at age 16, in 1914, after he had attended a concert where patriotic songs were sung and those in attendance were encouraged to march straight to the recruitment office. He was rejected as being too young on this instance, and left utterly heartbroken and humiliated. It seems particularly unfair, then, that just one year later he was surrounded in the street and mocked by women, who presented him with the dreaded white feather, meant to indicate cowardice in men who weren’t fighting for their country. Humiliated once again, Lovegrove visited the recruitment office a second time, and this time was accepted. He went on to serve with the Royal Field Artillery in Britain and the Royal Irish Fusiliers in Ireland, then with the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment and South Lancashire Regiment on the Western Front from 1917, where he took part in the Battle of Arras.

As well as pressure, patriotism and a wish for adventure played a big part in attracting boys to a life in service. George Coppard M.M, who joined up aged 16 and later wrote the book ‘With a Machine Gun to Cambrai’, said, “News placards screamed out at every street corner, and military bands blared their martial music in the main streets of Croydon. This was too much for me to resist, and as if drawn by a magnet, I knew I had to enlist straight away.” With children tending to leave school at age 14 at that time, there were few opportunities for young people to do exciting work or travel overseas, so it’s no wonder that the life of a soldier was attractive to many. Coppard, who joined the 6th Battalion Royal West Surrey Regiment, found himself in France by June 1915, and saw action at the Somme and in the Third Battle of Arras and the Loos offensive, as well as the Battle of Cambrai, of course. He nearly died as the result of a serious thigh wound.

Both of these boys were lucky enough to survive, unlike John (Jack) Travers Cornwell, who joined the navy aged 15 and was on board HMS Chester during the Battle of Jutland when German shells ripped a hole in her side, wrecked her after control and destroyed three of her 10 guns. According to ‘Deeds that Thrill the Empire, Vol V’, Jack was the only person, other than an officer, mentioned in despatches by Admiral Sir John Jellicoe and Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty directly after the battle. Beatty wrote,

“A report from the commanding officer of the Chester gives a splendid instance of devotion to duty. Boy (First Class) John Travers Cornwell, of the Chester, was mortally wounded early in the action. He, nonetheless, remained standing alone at a most exposed post, quietly awaiting orders until the end of the action, with the gun’s crew dead and wounded all round him. His age was under sixteen and a half years. I regret that he has since died, but I recommend his case for special recognition in justice to his memory, and as an acknowledgement of the high example set by him.”

Cornwell was indeed posthumously awarded the country’s highest honour for valour under fire, the Victoria Cross. He is the third youngest recipient of the award ever, and the youngest of the 20th century.

The British weren’t the only ones using boy soldiers in battle at that time. The Germans famously set the ‘Kinderkorps’, specially created new units of young, inexperienced soldiers, two thirds of whom were aged 17-19, against the British ‘Old Contemptables’ in the First Battle of Ypres. ‘The First World War: a Miscellany’ states that one of the units suffered 75% casualties during this battle, so a large number of youths certainly died in the war. In fact, the official minimum age for soldiers in the German army was 17, so these troops weren’t even underage, and of course, the younger boys were allowed to join up, the greater the chance of accidentally recruiting a youngster pretending to be older. In both countries, it took some time for youngsters to realise that fighting in the trenches wasn’t fun, but horrific; similarly, it took the recruiters until 1916 to realise that the war wasn’t going to end quickly, and that young boys needed to be shielded from the fighting, as it was more likely to be the death of them than ‘their big chance’.

In World War Two, to start with German lads were not required to fight, the minimal age for joining the army being fixed at 18 years until 1943. However, Hitler began to indoctrinate the minds of young Germans in Nazi ideology from as early as 1933, when he banned membership to any youth organisation other than Hitler Youth. In ‘The War Illustrated, No 168, Vol 7’ in our Historic Documents Archive, Martin Thornhill, MC, writes,

“Well knowing the susceptibility of young minds, Hitler, assisted by his team of political, physiological and psychological experts, set to work to shape a new Germany which would offer itself, without reserve, to the Führer and his direction.”

Boys aged 14-18 were permitted to join, whilst those aged 10-14 signed up for German Youth, which fed into Hitler Youth. No wonder Hitler suspected the Boy Scout movement in Great Britain might be an undercover military arm; that’s what he was building. By 1939, many boys who had passionately followed Hitler for a decade were already of age to join the army, having received relevant training in the form of ‘fun’ activities, and their younger peers ached to join the fight as well.

They soon got their chance, as The Reader’s Digest’s ‘The World at Arms’ explains, first being required to fulfil the duties of men called away to the Front, serving their country by working as messengers, telephone operators, fire-fighters and hospital orderlies, or operating the anti-aircraft guns from age 14. From February 18, 1943, all men aged 16-65 not already serving in the army were called up for compulsory labour, with children as young as 10 taking over their home duties. Certain youths of 16 or over were drafted into the army proper and trained as part of the 12th SS Panzer-Division, Hitler Jugend. This division was unleashed on the Allied forces on D-Day, and soon earned a fearsome reputation. The boys played a massive part in defending the Falaise Pocket in August 1944, and were later found to have murdered 64 British and Canadian prisoners of war the same month. The average age in the unit was just 17, but Allied men described these youngsters as being every bit as zealous as devoted members of the SS.

‘The Last Escape’ by John Nichol and Terry Rennell includes an account of the evacuation of Luft VI, in July 1944, illustrating just how eerie the fanaticism of the young serving soldiers could seem: “Peering out into the gathering dusk the prisoners saw to their horror that their familiar guards had disappeared. Instead, along the track were lines of vicious-looking young men in white uniforms, brandishing unsheathed bayonets. They were Marine Cadets, a naval version of the fanatical Hitler Youth… Those inside the trucks saw hate in the eyes staring in at them, and feared for their lives. That night they slept little, kept awake by the sound of steel blades being sharpened on grinding wheels outside and the laughter of the youths as they boasted about how they would teach the Terrorflieger (Terror Fliers, a name for Allied airmen) a lesson tomorrow.”

Nor were these stony-eyed warriors the youngest that Allied troops would encounter. By October 1944 the Germans were already beginning to panic that they might lose the war, and another proclamation was issued, calling for all healthy men aged 16-60 left in the nation to become part of the Volkssturm, the ‘People’s Guard’, essentially a German version of our own Home Guard. Unlike the British Home Guard, however the new recruits would be forced to participate in the fighting before the war ended, and as Germany’s position became more and more desperate, this poorly trained and poorly equipped body began to welcome help from younger and younger boys, until 11 and 12 year olds were bearing arms. As ‘The World at Arms’ explains, “Allied troops were tempted to treat them like naughty schoolboys, but a rifle or a sub-machine gun was just as lethal in their hands as in those of a fully grown man.” Perhaps more so, as with age comes perspective. These children had never known anything but war and the rule and values of Hitler, and for them the idea of Germany losing was worse than anything they could imagine. From their point of view, having no dependents, it really was do or die, and they had nothing to lose. Many youngsters were enlisted as suicide squads, and carried out their ‘duties’ without a trace of hesitation.

Meanwhile, in Britain the Home Guard accepted boys aged 17 and up, but of course these lads were lucky enough never to see action. The cadets of most services, similarly, never made it overseas. The only active organisation that let in younger boys was the Merchant Navy, which accepted recruits aged 16 and up; many boys of course still slipped in by lying about their age, such as Raymond Steed and Reginald Earnshaw, who were both killed in action aged 14, but generally recruiters were far less likely to willingly let youngsters sign up to fight than they had been in 1914. The Great War had demonstrated just how bloody, miserable, heart-wrenching and unrelenting being involved in a world-wide conflict could be. Few figures in authority, then, could stomach the idea of knowingly sending British children off to war.