Military Genealogist Simon Pearce has been exploring our Coronation medals collections and delving into the stories of some of the recipients of the 1937 and 1953 medals.

A Coronation is a significant moment in the early stages of a monarch’s rule, and since 1066, the Coronation of each British monarch has taken place at Westminster Abbey. The Coronation of His Majesty King Charles III and Her Majesty The Queen Consort is the 39th Coronation ceremony to be held at Westminster Abbey. But how can Coronations help us to learn about our ancestors?

Over the centuries, medals have been issued to mark a monarch’s Coronation. The first medal to be issued in England marked the Coronation of Edward VI in 1547. Moving forward in history, King George V’s 1911 Coronation Medal was the first to be awarded to individuals not attending the ceremony. Recipients of Coronation medals include civilians, in addition to members of the armed forces from Britain and the former British Empire.

As military family historians, we’re fascinated by the medals issued at each Coronation and what the records behind them tell us about our ancestors. Keen to learn more, we identified four recipients from our 1937 and 1953 Coronation medal collections in addition to our London Gazette Military Awards, 1919-1939 collection. Read on to discover their stories.

Ronald Eugene Worrall Hastain (1908-1972)

Award: Queen Elizabeth II 1953 Coronation Medal

Organisation: National Federation of Far Eastern Prisoners of War Clubs and Associations.

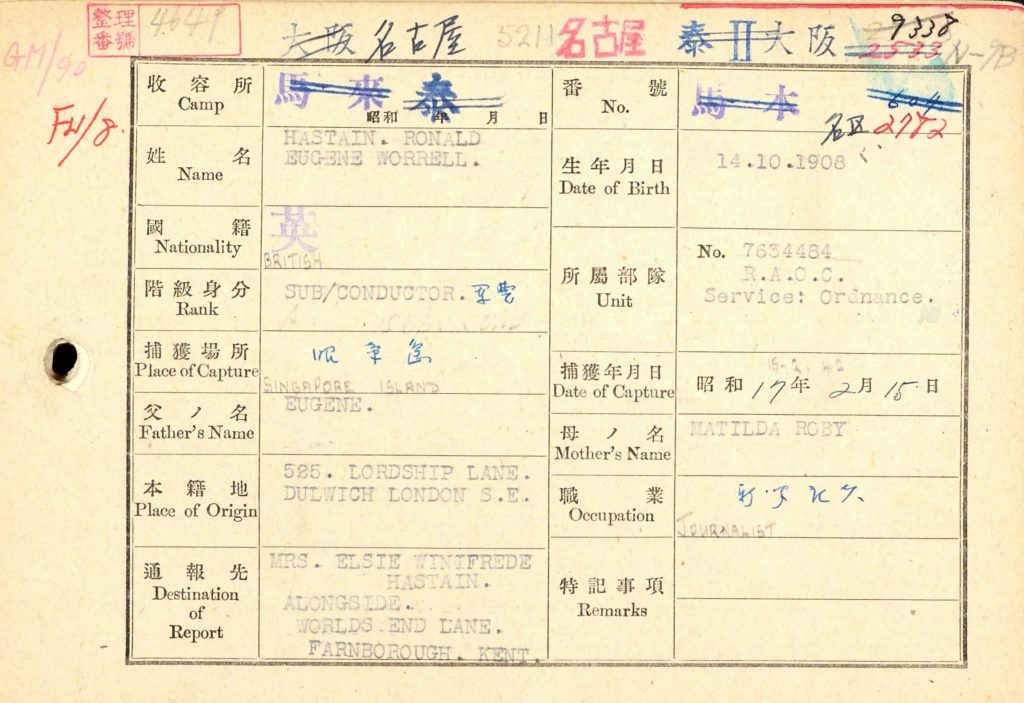

Ronald Hastain was a journalist before the Second World War and lived in West Sussex. He enlisted in June 1940, two days before German troops entered Paris following their swift occupation of Western Europe. Ronald served with the British Army in the Far East as a Sub Conductor (senior Warrant Officer) in the Royal Army Ordnance Corps. Ronald’s war drastically turned in December 1941 when Japan attacked Pearl Harbour and declared war on Britain and the United States. Allied forces battled to thwart Japan’s rapid advance in the Far East and Pacific. British territorial possessions, such as Hong Kong and Singapore, were soon in Japanese hands.

An article from the Leicester Mercury, available on Newspapers.com, suggests Ronald was attached to the 1st Battalion Leicestershire Regiment when Singapore fell on 15 February 1942. 80,000 British and Commonwealth troops were rounded up by Japanese forces, leading the Prime Minister Winston Churchill to describe it as “the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history”.

Ronald was among the prisoners taken at Singapore, as seen in our Allied Prisoners of War, 1939-1945 collection, a useful resource for researching WWII prisoners of war. He was initially held at Changi Camp, located in the northeast of Singapore, and later transferred to Thailand, where he and other Allied prisoners were used as forced labour to build the Burma-Thailand Railway. Despite contracting cholera and malaria, Ronald survived this ordeal. Following his liberation after Japan’s surrender in August 1945, Ronald, like many of his compatriots, was repatriated home to the UK via Canada.

After the war, Ronald published a book on his experience as a POW. He later became the chairman of the London Committee of the National Federation of Far Eastern Prisoners of War Clubs and Associations and deputy chairman of the national federation. The organisation successfully campaigned to compensate former Far East prisoners of war or their next of kin. Ronald’s is just one of many entries in our collection relating to the Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal.

Mildred Beatrice Veal (1922-2014)

Award: Queen Elizabeth II 1953 Coronation Medal

Unit: Women’s Royal Army Corps

Hull-born Mildred Veal was a Captain with the Women’s Royal Army Corps when she was awarded the Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal. The unit was formed after WWII, encompassing serving members of the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS). Over 250,000 women served with the ATS during WWII, initially carrying out roles such as drivers, orderlies and clerks attached to army units. Opportunities were expanded as the war progressed, and new roles became available.

During WWII, Mildred served as a gunner with the ATS, joining as a 19-year-old volunteer in February 1941; wartime conscription for women was introduced in December that year. Mildred volunteered during the Blitz, the German bombing campaign that devastated towns and cities across Britain. Although the Blitz ended in April 1941, subsequent bombing attacks, particularly the V1 and V2 rocket attacks of 1944-1945, caused significant loss of life and damage.

From 1941, ATS gunners like Mildred worked in mixed anti-aircraft batteries of the Royal Artillery. While women were not permitted to fire the anti-aircraft guns, they performed vital work within the batteries. Mildred specialised in tracking enemy aircraft using radar and took charge of radar systems at various stations in Britain, including Plymouth. Here, she helped to protect Allied troops during the D-Day landings of June 1944. Subsequently posted to London, Mildred served in connection with combatting the V1 and V2 rocket attacks. V2 rocket attacks alone claimed the lives of an estimated 9,000 people.

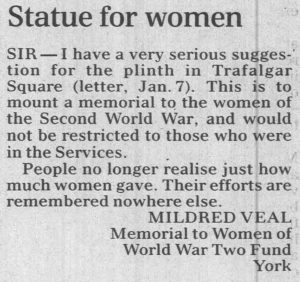

In the late 1990s, Mildred, along with fellow gunner Edna Storr, led a campaign for a monument to be dedicated to women who served during WWII. The campaign received attention in local and national papers, particularly in Mildred’s native Yorkshire. Mildred told the Daily Telegraph:

“The women in the war did a lot of very good work. Many of them died doing that work and they should be remembered.”

Their determination paid off, and in 2005 the ‘Monument to the Women of World War II’ was unveiled in Whitehall, London, by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

Frederick Oswald Aarons (1887-1984)

Award: Appointments made in honour of the Coronation of King George VI in 1937

Organisation: New South Wales Blinded Soldiers Association

In addition to medals, appointments were conferred in connection with a monarch’s Coronation. Australian Frederick Aarons was made an MBE (Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire) in connection with the Coronation of King George VI in 1937. The award was most likely in relation to Frederick’s role as President of the New South Wales Blinded Soldiers Association. We discovered that Frederick had a very personal connection to the organisation.

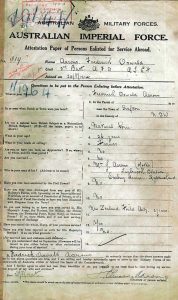

Frederick enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) on 24 August 1914, less than three weeks after Britain had declared war on Germany. Despite efforts by the Government, conscription was never introduced in Australia during WWI. Frederick was posted to the Australian Field Artillery as a Gunner and left Australia for training in Egypt in October.

On 25 April 1915, Frederick landed on the Gallipoli Peninsula during the Allies’ ill-fated Gallipoli campaign against the Ottoman Empire; 2,000 of the 16,000 Australians and New Zealanders who landed on the beaches of Gallipoli on that date were killed or wounded. A competent soldier, Frederick made his way up through the ranks receiving a commission as a Second Lieutenant in November 1915. On 12 December, as the Gallipoli Campaign was drawing to a close, Frederick received a devastating blow in the form of a gunshot wound to his right eye and a fractured right shoulder. Damaged by fragments from a high explosive shell, his right eye required removal. Three days after Frederick was wounded, the evacuation of ANZAC Cove began, and Allied soldiers were gradually withdrawn from the peninsula. Estimates suggest between 7,500 and over 8,100 Australian soldiers died during the campaign.

Frederick was hospitalised and departed Suez for Australia in late January 1916. A medical board in Egypt recommended Frederick for discharge as permanently unfit for military service, and he was discharged in May. Despite losing his right eye, Frederick re-enlisted and was promoted to Captain in September 1916. The following month, he departed Australia once more for overseas service with the Australian Field Artillery. Frederick was stationed in England for two months on the way to the Western Front, which he reached in January 1917.

His eye injury continued to cause him problems, and Frederick suffered from inflammation of the connective tissue in his right eye socket, and he was hospitalised and returned to England in August. Unfit for further active service, Frederick returned to Australia in late October, suffering from defective vision. On 15 February 1918, Frederick’s appointment with the AIF was terminated.

After the War, Frederick became a member of the League of Nations Union, volunteered as secretary for the Rural Employment Scheme for Boys, was President of the Australian External Affairs Society in Sydney and was President of the New South Wales Blinded Soldiers Association.

Minnie Sage (born 1895)

Award: Queen Elizabeth II 1953 Coronation Medal and King George VI 1937 Coronation Medal

Organisation: Royal Air Force Institute of Pathology and Tropical Medicine

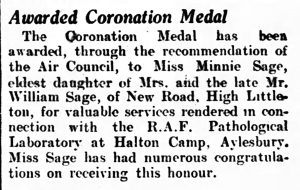

Minnie Sage was the recipient of both the 1937 and 1953 Coronation medals. A Civil Servant in the Air Ministry, Somerset-born Minnie was an Experimental Officer at the Royal Air Force Institute of Pathology and Tropical Medicine. After discovering Minnie in our Coronation medal collections, we delved deeper into her story to learn more about her fascinating work in connection with the armed forces.

We identified Minnie in our collection relating to civilian honours of WWII, a valuable source for learning about the awards gained by civilians for their wartime work. In 1946, Minnie was awarded the British Empire Medal (BEM) in the New Year Honours List. The award recognised Minnie’s meritorious services rendered in the Department of Pathology (RAF Medical Services) at Halton Camp, Buckinghamshire. The camp also contained Princess Mary’s RAF Hospital, both of which closed in 1995.

A newspaper article published at the time of Minnie’s BEM award noted her many years of service to Pathology, particularly in connection with the study of malarial parasites in the blood during both world wars. This was vital work, particularly given the impact diseases such as malaria had on the fighting capabilities of armies. During the Salonika Campaign of WWI, over a quarter of Allied forces were struck down with malaria. References to Minnie in newspapers, and the vital clues held within the articles, highlight the importance of newspapers when researching our military ancestors.

Sources

HANSARD 1803–2005: https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1999/oct/28/women-war-memorial, accessed May 2023.

British Museum: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/C_G3-EM-1, accessed May 2023.

Imperial War Museum: https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/second-world-war-weapons-that-failed, accessed May 2023.

National Army Museum: https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/auxiliary-territorial-service, accessed May 2023.

National Museum Australia: https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/gallipoli-landing, accessed May 2023.