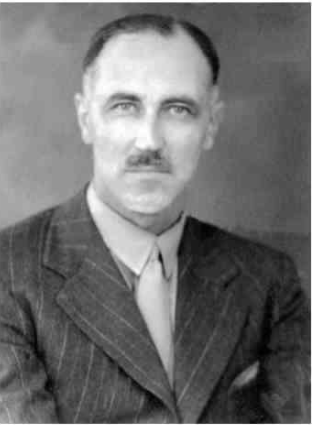

Submitted by his son, Nigel Crawford, this is an extract from the exclusive personal diary of Brigadier Kenneth B S Crawford, Royal Engineers, who fought in the Mesopotamia Campaign (now Iraq) from November 1914 until his capture in April 1916 at Kut-al-Amara. The Seige of Kut-al-Amara came about when the British Expeditionary Force was beaten back from capturing Bagdad and forced to retreat to Kut. The country was at the time part of the Ottoman Empire, and Turkey and Germany joined forces to pin down the British army. Despite many attempts to relieve it, the sheltering army eventually ran out of supplies and was forced to surrender, in what was a great blow to the British and a huge morale booster for the Turkish army:

Things were going badly with us inside the Kut perimeter. We were assailed chiefly by various intestinal diseases resembling cholera, and were burying from 30 to 50 men a day, latterly as many as 80 in a day. Efforts to send us food by air failed owing to the shortage of aircraft, and enemy interference. It took a fortnight to send us one day’s ration. From 24 January 1916 we had been on three quarters rations and the meat issued was either horse or mule. For some time after that the Indian troops refused to eat this meat. The ration was gradually reduced, and by 9 April we were down to 5 ounces of bread, and by 17 April to 4 ounces, with a similar quantity of meat. By this time nearly all the Indians were eating the meat issued. At least, they agreed to eat the horses – the British had to eat the mules.

The Arab inhabitants were trying to escape by swimming down the river at night. Unfortunately for them the Turks lined the riverbank, so they were nearly all shot and killed in the water when daylight came. As for the garrison, the average man’s temperature was down to 96° and his pulse to 55; a few minutes work exhausted him.

By 27 April no food was left, Townshend began negotiations with Khalil Bey, the Turkish commander, and on the morning of 29 April the Turks were allowed to march into the town. Our force, consisting of 400 British officers, 2700 British soldiers, and about 9000 Indian officers and men, was taken prisoner. After the officers and other ranks had been separated into different groups, they were marched off to the Turkish camp 7 miles up the river. I was amongst the wounded, who with the sick remained in Kut for another fortnight.

At the beginning of our captivity the words with which we were greeted by almost every Turkish officer we met were: “You are our honoured guests!” In view of the rough time we had during our journey up into Asia Minor, which took four months in my own case, and in view of the number of deaths that occurred, these words became a standing joke amongst the prisoners and were always brought up at our various dinners and meetings after the war.

Townshend tried hard to get the Turkish commander to agree to let the whole of the Kut Force go back to India on parole; though there is no reason whatever to suppose, even if Khalil Bey had agreed, that Townshend could have persuaded the Indian Government to allow such a thing (it might have affected the morale of Indian troops in tight corners elsewhere). Khalil Bey’s reply was that the surrender must be unconditional, but that if Townshend would refer the matter to the Turkish Government on his arrival at Constantinople, he might get what he wanted.

And so they packed him off as quickly as they could and Townshend went up the river – full of hope – in a motorboat, and was posted through to the Sea of Marmara, where they interned him on an island. Nothing ever came of the proposal for repatriation of the prisoners; but a few badly crippled officers and other ranks and about half the doctors were exchanged within three months of capture, under the Hague Convention. Townshend has been blamed for travelling on ahead of his troops on the line of march up to Anatolia but, apart from the question of whether he had any choice, it is doubtful whether this really made much difference to them.

His second-in-command General Mellis did take up very strongly with the Turks the bad treatment of the other ranks and secured some improvements – but the improvements came rather late and the Turks soon got tired of Mellis, and sent him off by himself in a carriage by the Euphrates route so that he saw no more of the prisoners.

As soon as the prisoners arrived in the Turkish camp near Kut, they were handed out the Turkish ration of small round loaves of black bread. These loaves were about the size and shape of a large thick biscuit; 5 of them made up the full bread ration. In the field, the Turks baked their bread away back at the base and sent it up to the front in sacks, usually weeks old, and it was so hard that it had to be soaked before one could eat it. We didn’t know this and in any case it was pretty poor sort of fare for stomachs that were mostly in bad order. Of the prisoners who entered the Turkish camp that morning nominally fit – that is not on the sick list – 91 were dead the same night. It is necessary to be very, very careful when making a complete change of diet like that, unless one is in perfect trim.

The Turks made a very great difference between their treatment of officers and their treatment of other ranks. The officers travelled up to Baghdad in barges, and were allowed a suitcase and a roll of bedding each. But the men had to march, as there was no railway. They could take with them only what they could carry. Beyond Baghdad there was a 17 mile length of railway which took them on to Samarra; but after that all ranks had to march about 200 miles across the desert in the middle of the hot weather before reaching the railway on the far side.

Officers on the march were allowed a pack animal between two to carry their baggage, but the other ranks had to carry their kits, and were flogged along with whips by the Arab guards if they fell behind at all. Hundreds of them couldn’t keep up, and died of cholera or dysentery by the way. In two places there were long marches of 30 miles or more without intermediate watering places. So many men died on these marches that the later parties coming after them were taken round another way, so that they shouldn’t see the bones of their comrades by the roadside.

There was a Gurkha battalion in Kut (the 2/7). These little men accomplished the whole distance marching as a battalion in formation under their Gurkha officers; which was a very fine performance in the circumstances, and a great help to the weaker men amongst them. It was most inspiring to see such a good regimental spirit.

The sick and wounded travelled by water from Kut to Baghdad, a distance of 200 odd miles as the river goes, and arrived there about the middle of May. I was with 3 sick officers – 2 British and 1 Indian – almost the last party to go through, and a very small one. From Baghdad we went on much as the others had done before us. Sick and wounded officers were supposed to have animals to ride, but they usually joined us onto convoys of sick soldiers and we had to give up our riding animals to men who were very badly in need. We had one long march of 32 miles, which we had to do without refilling our water bottles. It was hot weather and we usually marched about four hours in the morning and four in the evening. When we came to Mosul we had 5 days’ rest.

Eventually we reached the far railhead at Ras al-Ayn, and travelled the rest of the way in third class railway carriages, except when passing the two mountain ranges – the Taurus and the anti-Taurus – one of which we crossed in carts and the other in German lorries. The Germans were driving railway tunnels through those two ranges. As unskilled labour they took British prisoners for one tunnel, and Gurkhas for the other. I reached my prison camp at Afion on 27 August 1916– four months after the fall of Kut – and found myself along with 50 British and Australian officers captured at the Dardanelles (including 10 naval officers). There were also 80 Russians and a dozen Frenchmen.

The accommodation was adequate – each officer got about the same space as Generals and Brigadiers got at Shirakawa – but in addition each mess of 10 officers had a dining room, a kitchen, a store and a closet. Almost the whole of Asia Minor is at least 3000 feet above sea level and the mountains go up to 10,000 feet. Afion is in the centre, about 120 miles south-west of Angora. The summers are warmer than in England, and the winters are much colder. We were usually allowed out of our camps three times a week for a couple of hours with a sentry, to go shopping or walking, and were allowed 3 British orderlies for every 10 officers. Officers received pay at five shillings a day, and bought their own food. They received no rations.

Other ranks received a ration of bread, meat-soup, salt, sugar, coffee and tobacco; but drew no pay, except occasionally a little workingpay. The NCOs and men at Afion were housed in the Armenian church, which was a mighty cold place in winter, and they suffered a great deal from influenza, asthma, pneumonia etc. I saw as many as four bodies in a day carried past our houses for burial. Of the British NCOs and soldiers captured in Kut, 4 out of 5 died in captivity – about half the deaths were from intestinal diseases in the hot plains of Iraq, and the remainder mostly from chest troubles during the severe winters in Anatolia.

We could buy Turkish leather shoes (boat-shaped things with no laces), rough Anatolian stockings, cotton stuffs and thick white felt, out of which warm waistcoats could be made. The Ambassador also produced warm clothing, sent by the Red Cross. The Protecting Power was the USA during our first year. After the Americans came into the war, the Dutch Ambassador took over the job. We received most of our letters from home and about half our private parcels; and we wrote a short letter to our people once a month.

I spent a year and 9 months at Afion and then went to another camp between that and Smyrna where I passed the last 5 months of the war. About 60 of the officers at this other place were in a barracks just outside the town, and we were all out of the barracks one night, attending an amateur performance of the musical comedy “Theodore and Co.”, when a fire started in the middle of the town. It was a town of 20,000 inhabitants or so and densely populated. Turkish houses are built in wood frames to allow for earthquakes, the firefighting arrangements are primitive and when a town catches fire it is extraordinarily hard to put it out. By next morning this town had been almost entirely burnt to the ground. 35 officers (including myself), who lived in houses in the town, lost everything. I was left with what I stood up in – a cotton suit, SCWB warm overcoat, Turkish shoes, two small drinking glasses and an empty brandy bottle.

Towards the end of our captivity conditions eased up a good deal, and we were allowed to roam about within certain limits without a guard. The fire took place on 28 September 1918, and we were on the way to a new camp when the Armistice with Turkey was declared on 1 November. We were diverted without delay to Smyrna, where we waited for British ships to take us home. I sailed from Smyrna with a shipload of other prisoners on 18 November; and after a fortnight in Egypt and 7 days in a train crossing France, I reached my home a week before Christmas.