How sharing a letter from WW2 led to an emotional journey of discovery and shone a spotlight on a poignant story

When Forces War Records community member Jo discovered a letter from a soldier serving in WWII in her late grandmother’s possessions, she was determined to discover who the soldier was and share the letter with his family. But first, she had to find them, so she contacted our Military Genealogist, Simon Pearce. This is the story of John Merritt Wentworth and Dora Wheeler, writer and recipient, two lives greatly impacted by the devastation of WWII.

Surviving the Blitz

“I believe my Nan was living on Haydons Road in Wimbledon at the time of the bombing, if I remember correctly, she was 15, so it would have been around 1940?”

My early conversation with Jo revealed a family experience of the Blitz that will have been familiar to many of our ancestors who lived in Britain during WWII. The threat of aerial bombardment by the Luftwaffe, the German air force, became a reality with the beginning of the Blitz on 7 September 1940 and placed many British civilians in towns, cities and industrial centres on the frontlines. With the Blitz underway, life was extremely precarious for Jo’s grandmother, who was living in the nation’s capital.

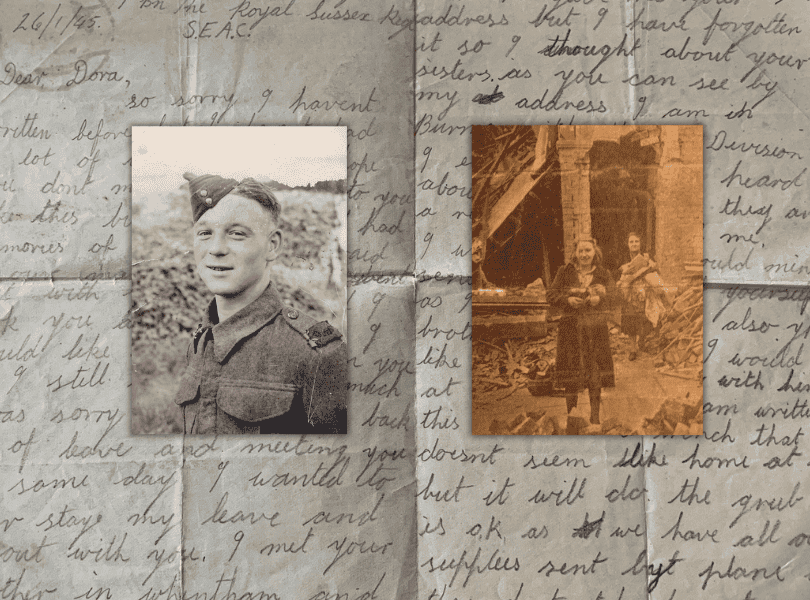

A folded newspaper cutting in Jo’s family collection transports the viewer back to those dark days of WWII. The striking photo, the focal point of the cutting, reveals Jo’s 15-year-old grandmother, Dora Wheeler, along with Dora’s mother, Maud. Both women are standing before their bombed-out home in Wimbledon, South London, with handfuls of possessions in their arms. Taking in the debris and piles of rubble, it is remarkable that the inhabitants survived the ordeal.

Following the outbreak of war, Dora’s younger sister Jean had been evacuated to Clacton in Essex. However, Dora, who worked serving in a restaurant, her elder brother Alfred, and her parents still occupied the home in Wimbledon. Many years later, Dora told Jo and her sister that she was at home on Haydons Road with her mum and dad, helping in the kitchen, when the raid that destroyed their house started. They were writing letters at the kitchen table. In a nod to normality and a youthful desire to have fun despite the extortionary world events unfolding around them, Dora’s new dress was hanging on the back of the kitchen door, ready for a dance. When the bomb hit the house, it blew the door across the room, landing on her father, Thomas. Everyone was miraculously uninjured; “even the dress survived (which she was very happy about)”, recalls Jo.

The fact that Dora can muster a smile in the newspaper photograph during this most trying of situations is a testament to the determination and spirit of her generation. The home on Haydons Road was now uninhabitable, so the family had to find alternative accommodation. It is not known where they set up home, but appear to have remained in the area.

John and Dora meet

Less than a 15-minute walk away, at 39 Pincott Road, Merton, was the home of Dora’s elder half-sister, ‘Lallie’. On the same street, lived John Merritt Wentworth, the soldier who wrote the letter Jo discovered in her grandmother’s belongings. Was it the extraordinary events of the Blitz that led these two young Londoners to meet? And who was John?

John Merritt Wentworth

John was born in London on 15 June 1924, the son of Cecil and Mary. According to the 1939 England and Wales Register, available on Ancestry®, at the outbreak of the war, John and his family were living at 27 Pincott Road, and his father was employed as a basket maker. The family home was six doors down from Lallie’s house.

Too young to serve during the early stages of the war, John would have seen family, friends, and neighbours called up into uniform to do their bit. His time would soon come.

It is assumed that John and Dora met sometime following the Blitz bombing raid that displaced Dora and her family. Perhaps the family sought temporary shelter with Lallie on Pincott Road while they looked for a new home. We may never know the answer to this question. An acquaintance appears to have formed between John and Dora, with less than a year in age separating them. How well did they know each other? John’s letter to Dora sheds some light on these questions, as we will discover soon.

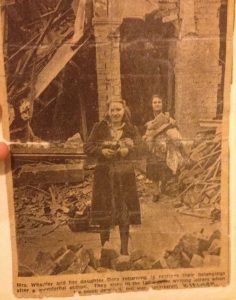

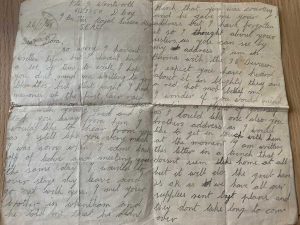

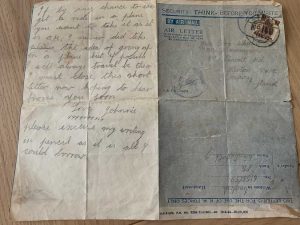

The letter

John wrote to Dora on 26 January 1945, composing his letter on H.M. Forces Air Mail paper with a pale blue envelope. As he did not know Dora’s address, he addressed his correspondence to the care of ‘Mrs Osborne’, Dora’s half-sister Lallie. This suggests Dora and the family may not have lived permanently with Lallie on Pincott Road following the loss of their house.

Sent all the way from Burma, though we are not sure exactly where, John’s letter offers a brief snapshot of this young soldier’s life at this important moment in the war:

‘I am writing this letter in a trench that doesn’t seem like home at all but it will do.’

How far removed the jungles of Burma must have been to a boy from South London.

Drawing on memories of life at home, John’s correspondence offers some answers to the questions about the youngsters’ relationship. The insight is intriguing and just enough to satisfy our curiosity, knowing there will be no other letters after this one. Studying John’s letter, he reveals that he was prompted to write to Dora following a strong memory:

‘I hope you don’t mind me writing to you like this but last night I had memories of the first air raid on our manor and you went out with young Fred and I took you away from him.’ Was there an air raid at that time in Burma which jolted this strong memory, or was he thinking about life at home?

John apologises for not writing previously and for composing his letter in pencil, as this was all he could find, revealing a thoughtful and considerate young man. He also requests a photo from Dora, perhaps offering comfort and familiarity during difficult times in an unfriendly and inhospitable place like the Burmese jungle.

Within the letter, John alludes to what must have been a heart-wrenching incident: bumping into Dora while returning from leave and wanting to stay longer so they could spend time together. It is evident that John had strong feelings for Dora at a time when life felt so precarious; it could be so short, and nobody knew what was around the corner. He signs off the letter with ‘Love Johnnie xxxxxxxxxx’, underlining his affection for Jo’s grandmother.

Dora carefully stored the letter away in her possession for decades, only for it to be revealed after her passing in 2020. The sentimental value of John’s correspondence is emphasised by its preservation for 80 years, as Jo highlights:

“…the letter must have meant a great deal to my nan to keep hold of it like she did. Looking at the dates, it’s not hard to understand why.”

This was most likely the last Dora ever heard from John. He died of wounds on 13 February 1945.

Tracing John’s descendants

Almost 80 years later, I received a message in my inbox asking if I could help trace the family of a fallen soldier whose poignant final letter had survived all these years. Using Ancestry® (Forces War Records is also part of the Ancestry® family), I was able to identify a person connected to John by studying their public family tree. It transpired that John’s nephew David had created the tree. David’s mother, Grace, is John’s younger sister. Jo subsequently contacted David and was put in touch with his brother, Rob, and discovered that 94-year-old Grace was still alive.

It was an emotional discovery. Grace believes it could be the last letter John ever wrote. Rob was able to shed more light on his mother’s reaction to the letter:

“My Mum described seeing the letter as heartbreaking but at the same time lovely to see as it was reassuring to know that John had someone special to think about other than the war.”

My conversations with Rob filled many gaps and provided me with poignant and valuable details, the kind you often only find by speaking to family. Let’s return to John’s story.

Filling in the gaps of John’s story

Grace and her siblings were evacuated from the family home in 1939 and sought refuge in nearby Byfleet, Surrey. Located close to Brooklands, housing important aircraft factories, their new home was not entirely safe from danger. The children returned to Wimbledon in 1944, just as the V-rockets were about to terrorise the nation. Rob and Grace agree that John and Dora most likely met after Dora’s home on Haydons Road was bombed. Grace was only 11 when John left to enlist, and her memories of him are vague. Rob, however, kindly provided a transcription from the MOD outlining John’s WWII service, allowing us to piece together his movements.

According to the transcript provided by Rob and his own remembrances, John enlisted on 23 June 1941, joining up in nearby Kingston upon Thames with his best friend, Bertie Tapping (Bertie survived the war, and Grace crossed paths with him in the 1960s). It was one week after John’s 17th birthday. Although conscription had existed since the beginning of the war, John would not have been called up until his 18th birthday; evidently, he was keen to do his bit.

John initially joined the East Surrey Regiment, serving with the 70th (Young Soldiers) Battalion, which included two companies of volunteers who were too young for active service and deployed on home defence duties. While conveniently stationed in Byfleet, John made the short journey to visit his younger siblings with their evacuee family. From November 1942 until mid-1944, John served with the Royal Army Ordnance Corps. In June 1944, he was attached to the 2nd Battalion Royal West Kent Regiment and, in September, landed in India, ready for his first taste of overseas service. According to Rob’s transcript, John was posted to ‘No. 1 Company 4 Wing’ in late October 1944.

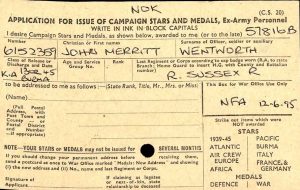

John was sent to take part in the fighting in Burma (now Myanmar). This brutal campaign in the unforgiving jungles and harsh terrain of Burma saw British and Allied forces pushed out of the country by May 1942. Subsequently, there was the failed Allied Arakan Campaign and the guerilla offensives carried out by the Chindits (British and British Empire troops). The Japanese attacks in Northern India at Imphal and Kohima in early to mid-1944, close to the Burmese border, were also repulsed. By late 1944, the Allies were in a position to launch their offensive, which would later see John drawn into the fierce fighting while serving with the 9th Battalion Royal Sussex Regiment, whom he joined on 26 January 1945, based on the MOD transcript provided by Rob. According to the battalion war diary held at The National Archives, on 26 January 1945, the battalion received 27 reinforcements from 26 Reinforcement Camp, Dibrugarh, which most likely included John.

At 08:30 on the morning of 13 February 1945, the battalion war diary notes that various companies of John’s battalion were on the move; we know from his letter that John served in ‘D Company.’ By 18:00 that evening, D Company were sniped by the enemy from the south side of a nearby river. The battalion war diary notes that one British Other Rank was ‘wounded, later died of wounds.’ This was almost certainly 20-year-old John Merritt Wentworth. He was subsequently buried in Taukkyan War Cemetery, modern-day Myanmar. John’s headstone reads:

‘Gentle in manner, patient in pain, Our dear one has left us, heaven to gain.’

Did Dora receive John’s letter after his death? How did she learn he had died? News would have travelled fast in these close communities where everyone knew each other. Grace remembered the other teens in Pincott Road who were around when the telegram arrived informing them of John’s death. Grace was only 15 years old when she heard she had lost her brother to the war. Grace thinks that Dora must have known about John’s death because Pincott Road was a close-knit community with just one shop at the end of the road; the loss of a local would have been a big talking point at the time.

Jo’s discovery of the letter in her grandmother’s possessions led to the unearthing of a poignant wartime story that was so personal to her family. John and Dora’s story emphasises the importance of keeping the memories of our military ancestors and those who lived through the wars alive. It’s especially important to remember those such as John, who made huge sacrifices, who didn’t get to live out all their hopes and dreams, and who gave up their tomorrow for our today.

The information in this blog regarding John Merritt Wentworth and Dora Wheeler is largely based on details and sources provided by the families in conjunction with official documents where possible.

Sources

Imperial War Museums, Listen To 8 People Describe The War In Burma In Their Own Words, accessed October 2024.

The National Archives, Catalogue description, accessed October 2024.