The Battle Of The Somme

On the, 1st July 1916, the Battle of the Somme commenced. Although nominally an Allied victory, this conflict is generally seen to epitomise the utter futility of trench warfare, and resulted in massive losses for the British- not to mention every other force involved. By the end of the battle, in mid-November 1916, Britain had suffered 420,000 casualties, France 205,000 and Germany at least 680,000. In the first day of fighting alone, the most deadly of all, over 20,000 Allied troops died and 10-12,000 Germans. The gain from these months of bloodshed? The Allied forces advanced 8km, or 5 miles.

So, what went wrong? Traditionally, Field Marshall Haig, the British Commander in Chief, has shouldered much of the blame. However, he is not the only one who contributed to what amounted to a veritable flood of errors by commanders on both sides.

The battle had two main aims to start with. The first was to divert German manpower and attention away from Verdun, East of Paris, where the French army was suffering extremely heavy losses, and in this alone the Allies can be said to have succeeded. The second, says Philip Warner in ‘World War One: a Chronological narrative’, was to overwhelm the Germans with enough force to allow the troops to smash through the German lines and advance rapidly across the plain beyond. Haig theorised that, even if the Germans were only driven off the plane, they would lose a great vantage point and their field of observation would be reduced, leaving the Allies tactically better off. With regards to this aim, the losses most certainly outweighed any benefits gained.

The first problem, says Warner, lay not with Haig, but with the French General Joffre. He was responsible for the position of the attack; Haig had wanted to attack further north, but Joffre persuaded him to change his plans, the better to fit in with Joffre’s own. While it is debatable whether Haig’s original plan would have been more successful, the sheer scope of the first day’s carnage lay to a degree at Joffre’s door. He carried the day when dividing up responsibilities; the French had originally agreed to attack on a front 25 miles wide, with 16 divisions. Mistakes at Verdun had led to the French forces being severely battered, to the extent that finally only 8 divisions could be spared, and they could only cover an 8 mile front, leaving the British to bear the brunt of the attack. This had originally been planned for the 29th June, but Joffre wasn’t ready, so it was pushed back; it had also been set to take place before dawn, but he rolled the critical hour back to 7.30am. The British troops had already endured two very uncomfortable days of heavy rain, being deafened by gunfire. Now, they were ordered to advance towards German lines in boiling heat and, worse still, bright sunshine. Their packs were so heavy that they couldn’t run, and they were in plain sight of every German machine gunner.

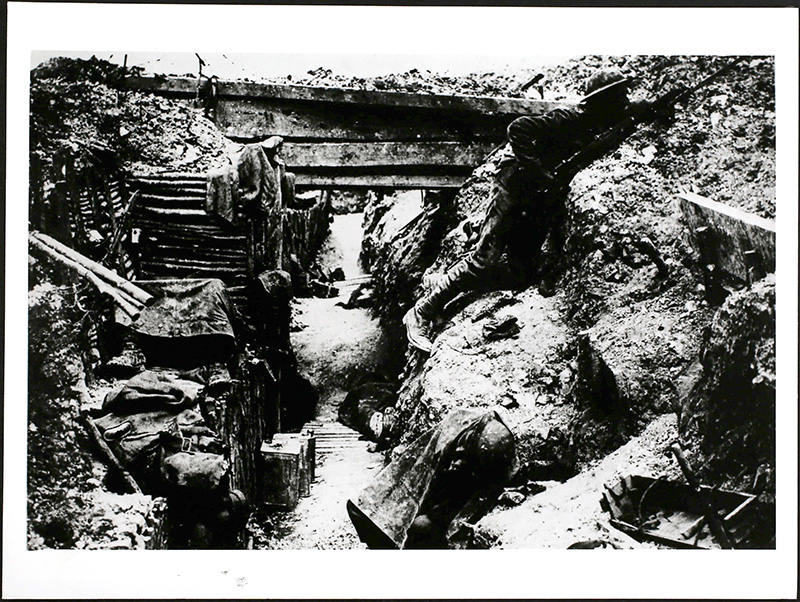

Here, several of Haig’s own mistakes came into play. First, he had woefully misjudged the strength of the Germans’ position. While Joffre had been in favour of a steady war of attrition, and indeed General Foch, the head of the French army, and leading British commanders such as General Henry Rawlinson, always believed the battle would achieve little, Haig was all for urging the available forces into an all-out assault. The idea had been to lessen the battering the troops would have to endure by first raining the Germans with a weeklong artillery barrage, in an attempt to decimate their ranks. However, the Germans had by this time been in the area for two years, and had built sturdy, fortified trenches, surrounded by several lines of barbed wire, as well as snug dugouts for just such an occasion. Accordingly, they swiftly retreated to the safety of the dugouts when the shelling began, and when it ceased and whistles blew to signal the start of the attack, calmly filed out again and took their positions behind the machine guns.

Haig’s second big mistake had been to listen to his colleagues. He had at first decided that it would be a good idea, after the artillery and before the infantry attack, to send small parties out to make sure the German barbed wire had been flattened, and cut it if not. His subordinate commanders thought this to be unnecessary, and pilots of the Royal Flying Corps, having surveyed the area, agreed. Multiple lines of barbed wire therefore greeted any troops who made it as far as the German trenches. However, not many did, thanks to Haig’s final mistake. He once again listened to his subordinates, who suggested that poisoned gas would do more harm than good, and smoke would run the risk of confusing the troops and preventing them from reaching their ultimate goals. It is true that most of the men were inexperienced, many having only just joined the army as a result of Lord Kitchener’s recruitment drive. For many this was their first battle, and they were sitting ducks: heavily weighted, unaware of the limited effects of the artillery barrage and the extent of the defences lying between the Germans and themselves, and plainly visible to every German gunner. The casualties were horrific.

Some miraculously reached the German lines. That first day 13 Corps reached Montauben, its allotted objective, Mametz was captured, and the 36th (Ulster) Division also reached its allotted objective and waited for reinforcements, who could have helped to exploit a short-lived weakness in the Germans’ defences. Many of the French troops made progress, having had more guns and met with less resistance, and waited for the British to back them up. However, reinforcements had in some cases been diverted, in others killed. No real gains were made that day as a result, and 19,290 Allied troops died, 35,493 were wounded, and 2,000 listed as missing.

Philip Warner’s ‘World War One: A Chronological Narrative’ explains that the final nail in the bloody coffin that was the Battle of the Somme was driven in by the German battalion commanders. The Germans were largely better protected, and should have suffered less casualties overall. However, the order had been given that immediate counter attacks must be launched to regain any ground lost, and that any officer who failed to do so, even for tactical reasons, should be court-martialled. So, during the months of fighting many a German soldier was needlessly thrust into harm’s way. This was truly a battle that brought nobody any good.

Follow in your ancestors footsteps using our interactive maps. You can use this to track the progress of units throughout the course of the First World War, from the opening battle at Mons to the closing stages of the Battle of Amiens.

First World War Orders of Battle Maps