The Atlantic magazine recently carried a story on ‘World War One’s Forgotten Female Shell Shock Victims’, and outlined the infamous case of Elizabeth Huntley, a British woman who decapitated her own daughter in late 1917. At her trial, friends testified that she’d been kindly and happy before the air raids on London started, while her sister described how the trauma of these attacks had caused her to shake and have delusions. Her doctor had tried to get her out of London and away from her family, being aware of the great stress she was under, but his concern came too late and she suffered a nervous breakdown, culminating in the murder.

The failure to recognise the signs of shell shock in women, and the reluctance of those in authority to treat those symptoms in the same way as they would in a soldier returning from combat, was a sign of the times. Firstly, everyone knew that woman was the weaker sex, and far more susceptible to stress. ‘Broken Men: Shell Shock, Treatment and Recovery in Britain 1914-30’ by Fiona Reid explains that ‘hysteria’ was considered to be largely a female condition, with the 1910 volume of Encyclopedia Britannica noting that it was primarily associated with women, Jews and Slavs. Worse, it was sometimes defined as being due to “sympathetic connection between the brain and the uterus”. That being the case, a ‘hysterical’ condition couldn’t be compared (let alone classified) with shell shock. Soldiers were considered to be brave and manly, especially in the early years of the war when all the troops were volunteered; they didn’t get hysterical… at least, not without due cause.

Initially, the whole condition of shell shock was in fact dismissed as a form of hysteria. The men who suffered from it were disgraced, and in some cases prosecuted or even executed for violent outbursts, dereliction of duty or desertion. A true military man would never react in such a way; anyone who did was patently unfit for the life of a soldier, and must be naturally unstable. It didn’t take long, of course, for the Royal Army Medical Corps to start taking the condition seriously as more and more men exhibited symptoms of emotional distress. However, the men had reason to be shaken. The best soldiers might not usually be affected by the pressures of war, but this was hardly a traditional war. Never before had man been pitted against technology in such a way, and the modern weapons might shake anyone up. The women weren’t facing this kind of trauma, though. No, their condition must be different from that of the soldiers.

Two things were wrong with this assumption; first, those making it misunderstood the condition of shell shock. According to ‘Broken Men: Shell Shock, Treatment and Recovery in Britain 1914-30’, Sir Charles Myers, a consultant psychologist with the British Expeditionary Force from 1915, first used the term ‘shell shock’ in an official capacity. It fit what were at first assumed to be the cause of the condition. This must be a physical wound, with the nervous injuries being the result of the ‘wind of a bullet (or shell)’. The noise of the blast was also considered to be a contributing factor. However, as Myers became more familiar with the condition he realised that it was actually a psychological affliction, and came to regret coining such an unsuitable and medically imprecise name for it. Many men suffering from shell shock had not been on the front, and had never been near a shell, so it was wrong to imply that only people on the front were susceptible. It was too late, though. The name stuck, largely because sufferers preferred it, a physical condition seeming to them both more honourable and easier to heal.

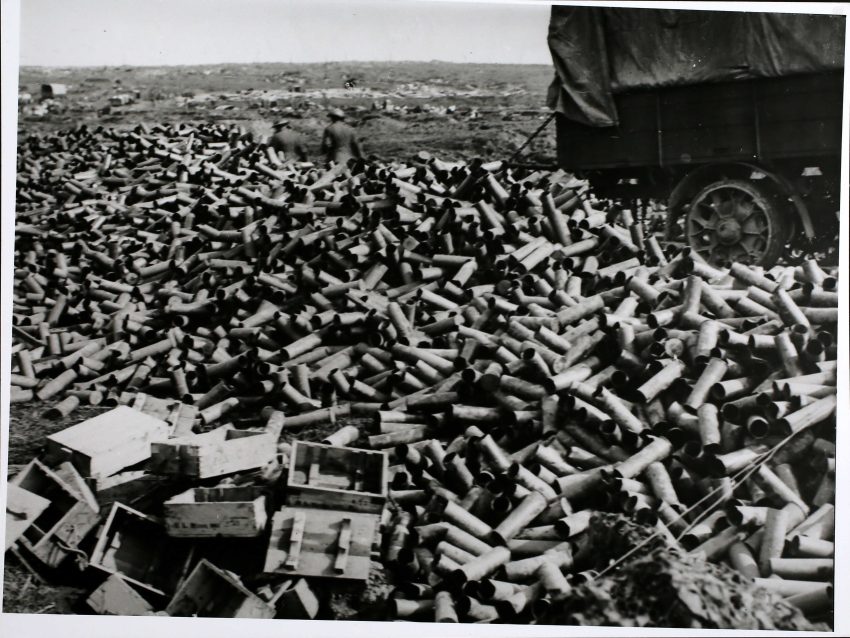

The assumption that shell shock and hysteria were different was also naïve since women were in fact facing many of the same ‘shocks’ as the men. ‘World War One: A Chronological Narrative’ by Philip Warner describes many ways in which women threw themselves into professions that by nature put them at risk. Fox example, filling shells with TNT could bring on all sorts of medical complaints, and explosions sometimes occurred, killing or injuring the workers. Ambulance drivers, meanwhile, were often out and about in the middle of air raids, braving bombs and recovering casualties in all sorts of horrific states. Even those remaining at home, such as the infamous Elizabeth Huntley, experienced considerable trauma, with the threat of bombing always in the back of their minds, and the effects- explosions, flattened neighborhoods’, mangled bodies and horrible suffering- plain to see.

Even assuming shell shock could only be experienced by those working on the Front, it is wrong to imagine that they were all men. Voluntary Aid Detachments were composed of 2/3 female recruits, and the growing shortage of trained nurses on the front meant that they started to be sent overseas. By 1917 over 8,000 female VAD recruits were to be found working in France, helping to patch up horrific injuries, and during the course of World War One over 38,000 VADs acted as ambulance drivers or worked in hospitals, whether home or abroad. They served in Mesopotamia, Gallipoli, and the Western Front. The First Aid Nursing Yeomanry was an all-female charity, and its members served as a first aid link between the field hospitals and the front lines. This exposed them to all the same dangers as the men, including shells, since they were so close to the action.

However, women were still not accepted as equal to men. ‘Broken Men: Shell Shock, Treatment and Recovery in Britain 1914-30’ notes that, although Ex Services Welfare Committee in theory widened its remit in 1920 to include the care of women who had suffered a mental breakdown as a result of military service, by 1923, when a Miss Vaughn, newly elected to the society’s committee, enquired whether women could apply for help from ESWC, nobody could remember if they could or not. Miss Vaughn had to write to London County Council to clarify this point, so it is doubtful than any women had been helped in the intervening years. What is certain is that, by October 1923, 71 ex-service nurses were being held in local asylums. There are just two recorded cases of women requiring long-term mental health treatment as a result of war service being aided by ESWC, and none of society’s care homes, intended to keep veterans out of asylums and facilitate their recovery from shell shock, accepted women- although the ESWC had actually been founded by a group of women!

It probably didn’t help that women were not permitted to work in the mental health services; at one point a Mrs Clarke, one of the founders of the ESWC, insisted that nurses should be invited to serve as advisors on the executive committee. A decision on the suggestion was deferred without explanation by Major Thwaites, the society’s doctor, and the issue was not raised again. Major Thwaites was not alone in thinking that women and mental health nursing were not compatible; Sir John Collie, one of the leading specialists in shell shock treatment, was said to be convinced that the influence of ‘kindly intentioned philanthropic visitors’ could be damaging to soldiers’ recovery, while Dr Brock, a temporary captain in the Royal Army Medical Corps, felt that too much coddling from a man’s own wife could lead him to become dependent, and consequently lack the willpower needed to overcome his condition. Again, women were seen as soft, ‘emotional’ and incapable of coping with the vigorous demands of the Armed Forces, despite repeated proof to the contrary.

It’s not surprising, then, that women were rarely treated for shell shock, since they weren’t considered to be manly enough even to suffer from such a condition in the first place. Elizabeth Huntley, who was eventually deemed “insane” and “unfit to plead” and sent to Holloway Prison, was described as having ‘air-raid shock’ rather than shell shock, while other women were said to suffer from ‘civilian war neuroses’. Whether consciously or unconsciously, both the government and the medical profession strove to help the male shell shock suffer to save face. He might not be manly enough to cope with the strains of war, but he had served his country after all and deserved respect. Nobody wanted to imply that he might have feelings in common with a weak and feeble woman.