Slapton Sands in Devon seemed the perfect place for the American Forces to simulate practice landings for the D-Day assault on Utah Beach, France on 6th June 1944. Though the operation was met with tragedy and a great loss of lives and was to remain a secret for decades to come.

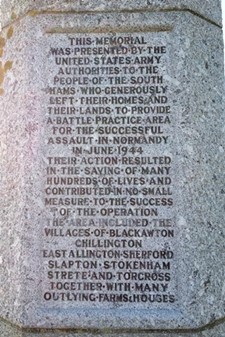

In 1943 the clearance of 30,000 acres and some 3,000 men, women and children in the areas around Slapton, Strete, Torcross, Blackawton and East Allington in South Devon were evacuated from their homes in order for the American military to carry out exercises.

The area around Slapton Sands was selected for these exercises because it had a great likeness to parts of the French Normandy coast, the location chosen for largest invasion by sea of the war – the Normandy landings. The whole point of the exercise was to make the dress rehearsal as realistic as possible. Dummy enemy positions were built alongside concrete pillboxes.

So vital was the exercise that Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower ordered the use of live naval and artillery ammunition. He wanted it to smell, look and feel like a real battle. He wanted the men to experience seasickness, wet clothes, and the pressure that comes with performing under fire and to accustom the soldiers to what they were soon going to experience in Normandy.

The exercise was conducted between 22nd and 30th April 1944 and commenced with the marshalling and embarking of the troops to the LSTs (Landing Ship Tanks) off the coast of south-west England. The first assault landings were made on the morning of the 27th April, following the ‘bombardment’ and was continued throughout that day. A follow-up convoy of eight LSTs was expected later that night.

Early on 28th April 1944, eight tank landing ships, full of US servicemen and military equipment, converged in Lyme Bay, off the coast of Devon, making their way towards Slapton Sands for the rehearsal.

However, unbeknown to the military, under cover of darkness, nine German E-boats (Schnellboot, or S-Boot, meaning “fast boat”) had managed to slip in amongst them in Lyme Bay.

The group of German E-Boats were alerted by heavy radio traffic in Lyme Bay and intercepted the three-mile-long convoy of vessels.

The heavily-laden, slow-moving tank landing ships were easy targets for the torpedo boats which first attacked the unprotected rear of the convoy. Two landing ships were sunk and a third badly damaged.

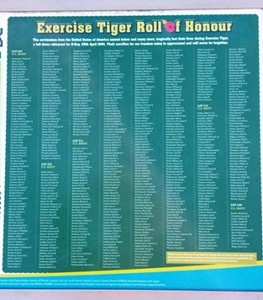

A series of tragic decisions – including the absence of a British Navy destroyer which was damaged in a collision during the night of the 26/27 April and was not on hand when the assault convoy was attacked, and an error in radio frequencies – led to three of the LST’s being hit by German torpedoes. Lack of training on the use of life vests, heavy packs and the cold water contributed to the disaster: many men drowned or died of hypothermia before they could be rescued. Over 700 Americans lost their lives.

Despite this, the rest of the exercise continued at Slapton beach, but with disastrous results. The practice assault included a live-firing exercise and many more soldiers were tragically killed by ‘friendly fire’ from the supporting naval bombardment.

The exercise was considered by US Commanders to be such a disaster that they ordered a complete information blackout. Any survivor who revealed the truth about what happened would be threatened with a court-martial.

Because of fears of its impact on morale, the terrible loss of life during the exercise was not revealed until long after the war.

An article in the ‘US Stars and Stripes’ magazine following the Second World War said family members of the dead were given no information other than what was in the original message about the death. The bodies of the G.Is who were killed were buried in complete secrecy.

Though, thanks to the training at Slapton, fewer soldiers died during the actual landing on Utah Beach than during Exercise Tiger, and so the training in Devon was not in vain.

Several changes resulted from mistakes made in Exercise Tiger:

• Radio frequencies were standardised; the British escort vessels were late and out of position due to radio problems, and a signal of the E-boats’ presence was not picked up by the LSTs.

• Better life vest training for landing troops

• New plans for small craft to pick up floating survivors on D-Day

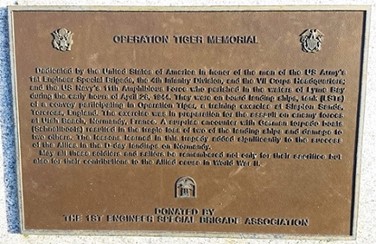

Exercise Tiger Memorial

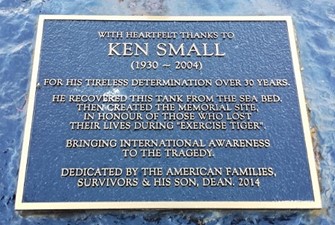

Devon resident Ken Small took on the task of seeking to commemorate the event, after discovering shrapnel, military buttons, bullets and pieces of military vehicles of the aftermath washed up on the shore while beachcombing in the early 1970s.

A close friend and local fisherman told Ken of an large object sitting on the seabed about three-quarters of a mile off shore 60 feet below the surface. Ken persuaded his friend to dive down and investigate. When he and the other divers came up, they told him there was an American DD, or Duplex Drive Sherman Tank (a type of amphibious swimming tank developed by the British during the Second World War) on the seabed. This discovery eventually led to him finding out about the tragedy of Exercise Tiger. He became determined to recover the tank and create a lasting memorial to honour those who perished.

After negotiations over several years, Ken Small bought the vehicle from the U.S government for $50, and finally recovered it from the sea in May 1984.

Now, 80 years on from its sinking, the tank has not only become a war memorial, but also the place to remember Mr Ken Small who died in March 2004, a few weeks before the 60th anniversary of the Exercise Tiger incident.

Mr Small told the story of Exercise Tiger and his discoveries in a book called ‘The Forgotten Dead’.

Thanks to his efforts, the Sherman Tank Memorial Site was officially recognized by the US Congress and acknowledged by the addition of a bronze plaque.